Instability of Meaning

Since the late 1990s, Peter Freitag’s artistic practice has developed around a consistent interest in images as carriers of intention, meaning, projection, and power. The starting point is always the already existing image, understood as a condensed bearer of meaning that conveys social notions, desires, and norms. A recurring idea runs like a red thread through his work: meaning is never stable; it arises in the act of attribution and can just as easily tip, disappear, or dissolve into emptiness. Within this tension, Freitag’s work operates with the instability of meaning: images seem to communicate something definite, yet simultaneously evade unequivocal readability, opening up spaces for projection, irritation, and reinterpretation.

Image Manipulation, Projection, and Psychological Charging (1998–2008)

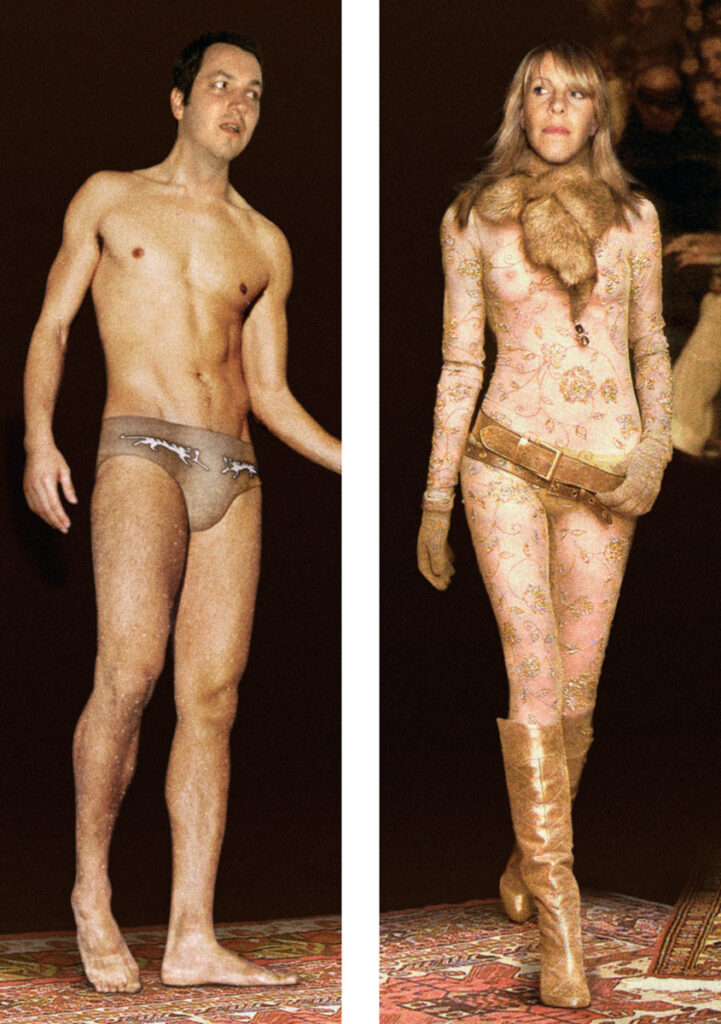

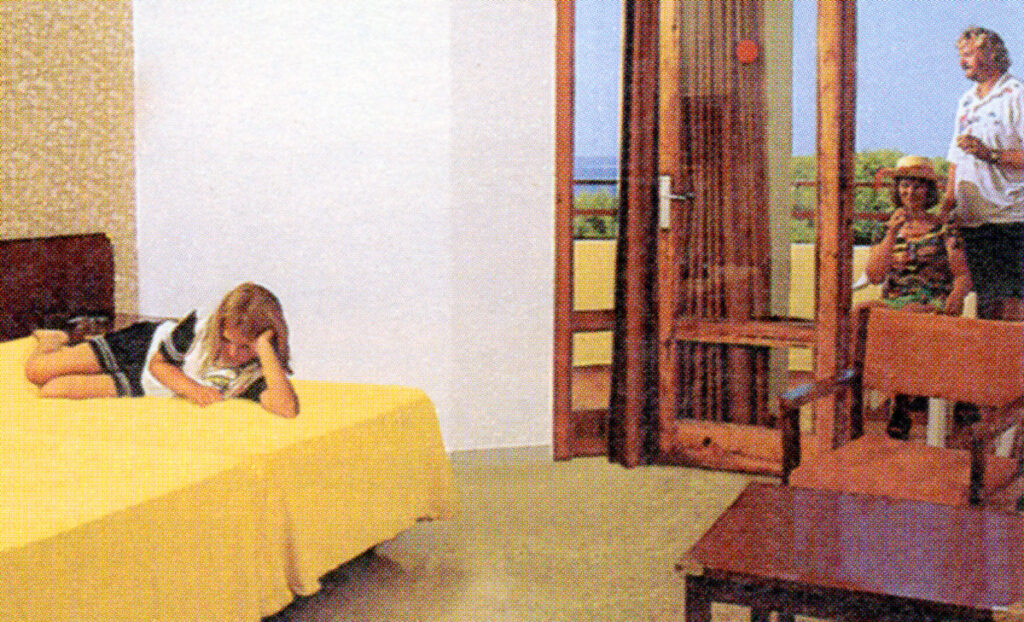

The beginning is a play with images from advertising and print media. In his Self-Portraits (1998–2008), Freitag mounts his own head on idealized advertising bodies, simultaneously elevating and profanizing them. Renaissance ideals, saintly veneration, and contemporary advertising aesthetics overlap, while the pixel structure of the source images exposes the artificiality of glossy images. Similarly, the Examples for Communication (1999–2002) employ minimal digital interventions to shift the intentions of the original images and create psychological tension. The viewer becomes part of the process, actively engaged in the attribution of meaning. Already here, staged, idealized privacy intersects with public advertising imagery and semi-public spaces such as hotel interiors.

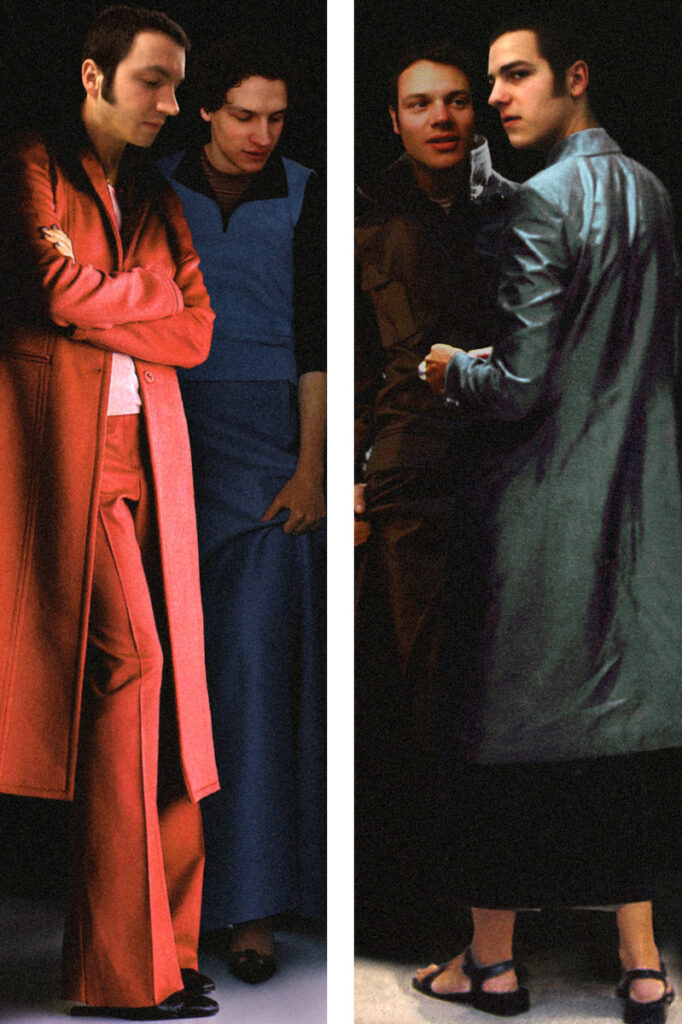

Scenes for Life (2006–2008) shift the focus from manipulated to constructed interaction within the pictorial space. Through photographically simulated collage and recontextualization, seemingly narrative scenes emerge, reminiscent of the logic of daily soap operas: always similar promises of meaning, yet without actual resolution. Meaning is constantly suggested but never fulfilled—a pictorial space in a mode of ongoing narrative without narration.

In these early series—Self-Portraits, Examples for Communication, and Scenes for Life—a central tension becomes evident: the confrontation between the everyday and art, between trivial and high culture. Images with apparently unambiguous function and readability are transferred into an art-specific context where their meanings become unstable and must be renegotiated.

Staged Privacy and Public Images (2003–2008)

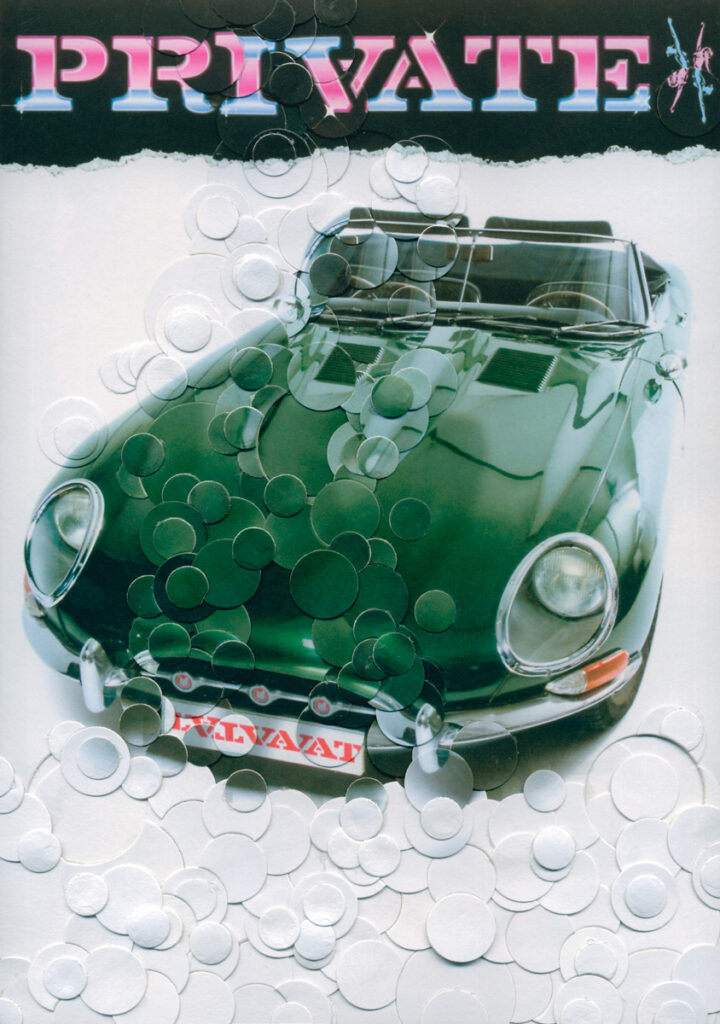

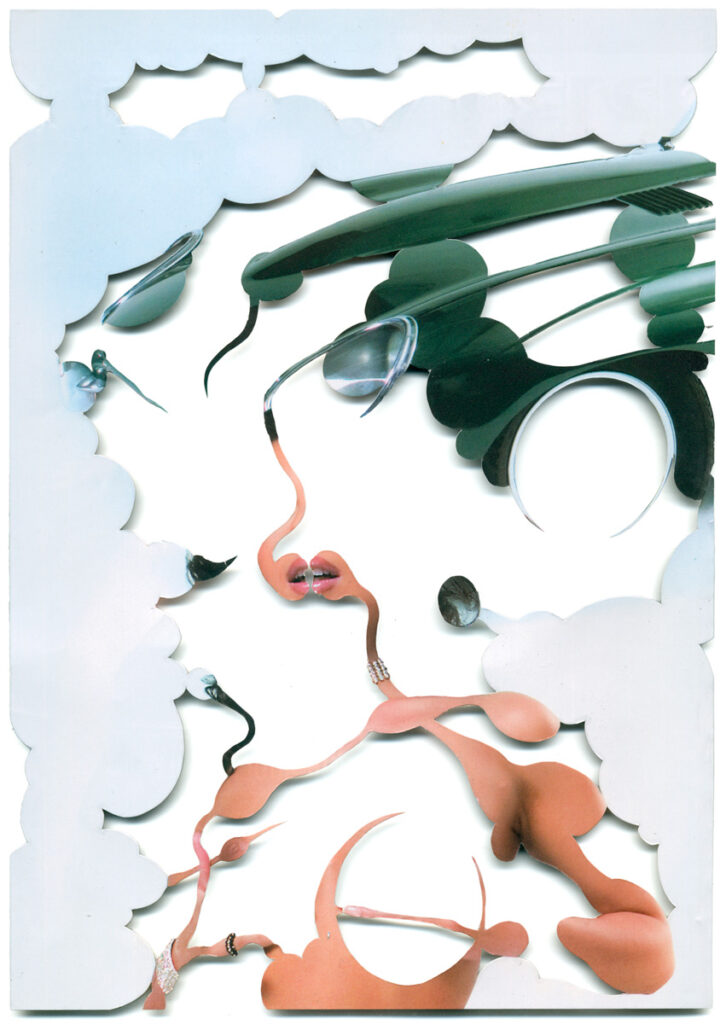

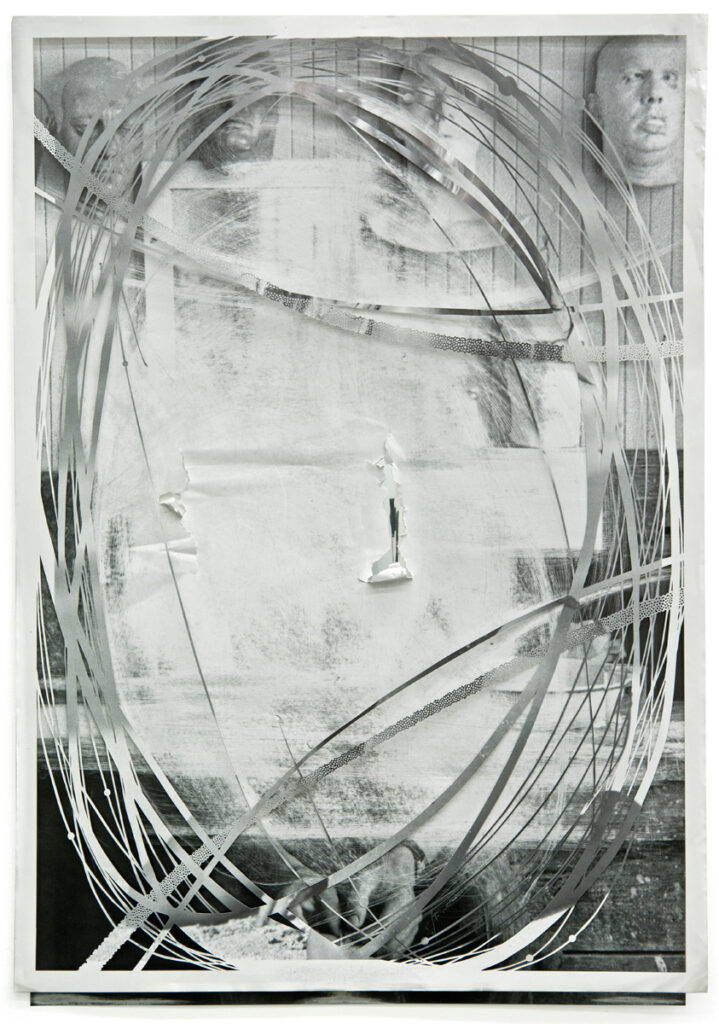

In the mid-2000s, Freitag intensified the focus already present in the Examples for Communication on the staging of privacy and its public display. Private Stages (2005–2008) consist of purely hand-made collages, deliberately drawing on digital image logics. Private or seemingly private pornographic sources are punched out and re-collaged. These works mark a first step back toward analog processes without abandoning the reference to the digital image world.

The series ebays (2003–2005) serves as a central point within this complex. Imagined portraits emerge from publicly accessible product images of individual users. Similar to Private Stages—where incidental glimpses of living spaces in the background of pornographic images provide an unintended insight into privacy—here too a picture of the private arises from the trivial: individual sales and purchase objects reveal originally unintended information about users’ circumstances, preferences, and routines. Visible pixel structures underscore the fragility and fragmentation of digital identity.

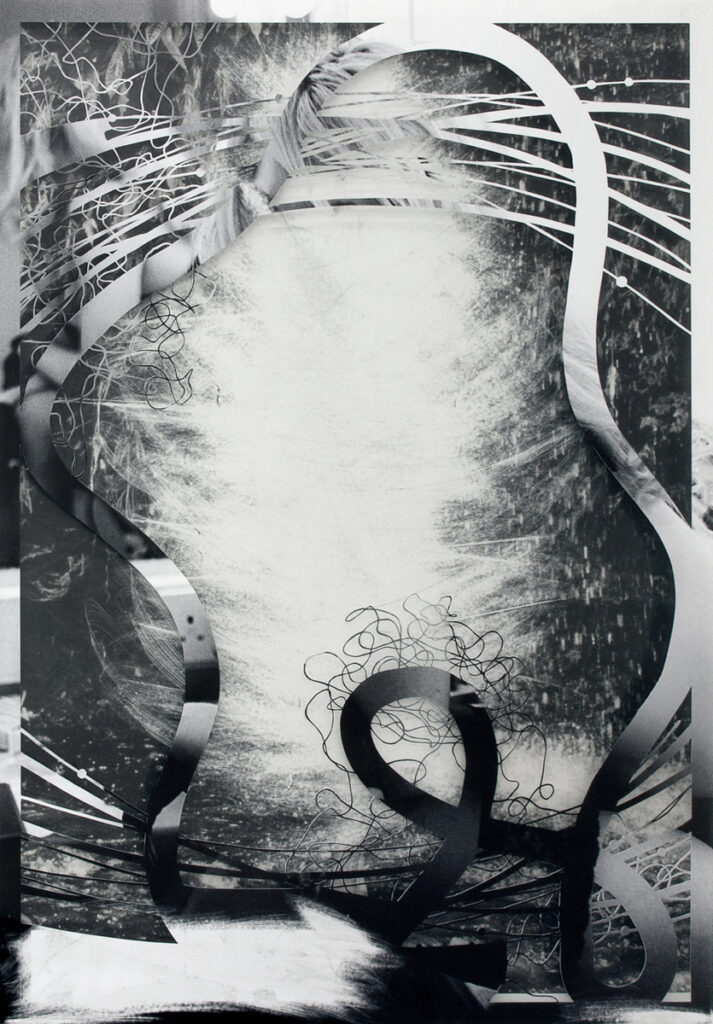

Papercut, and New Pictorial Space – Erosion of Meaning (2009–2012)

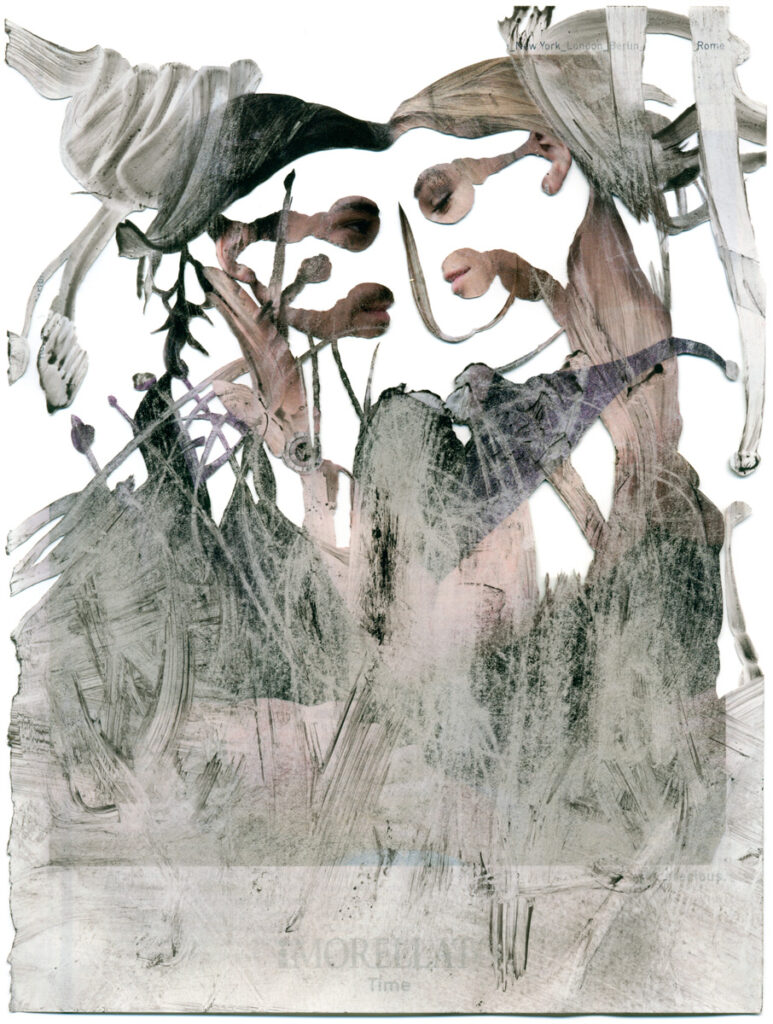

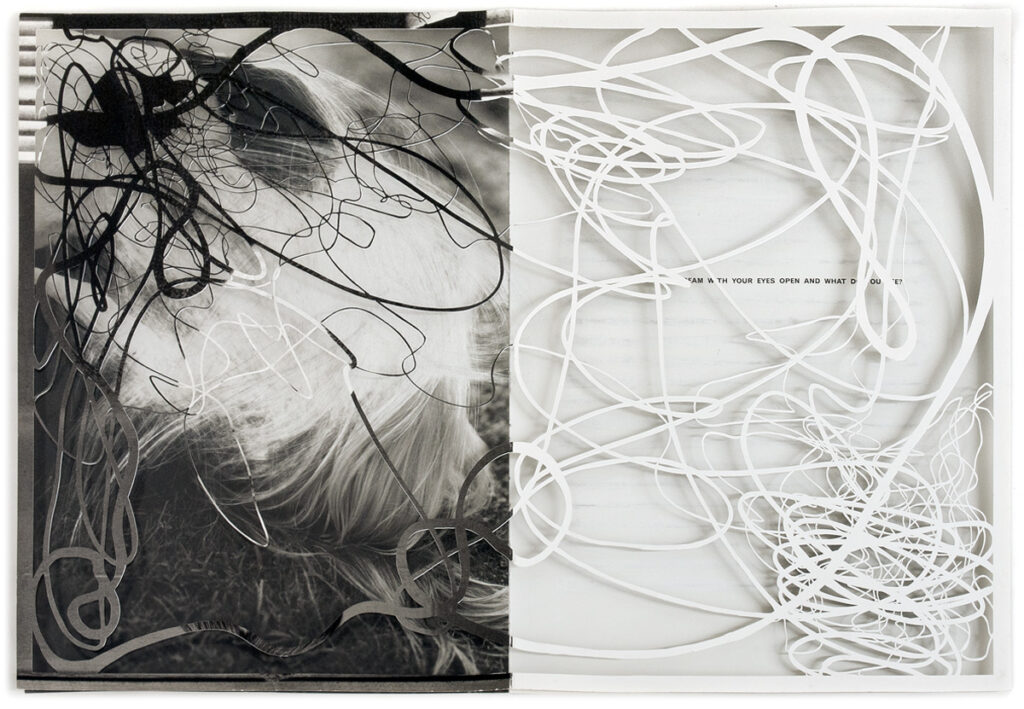

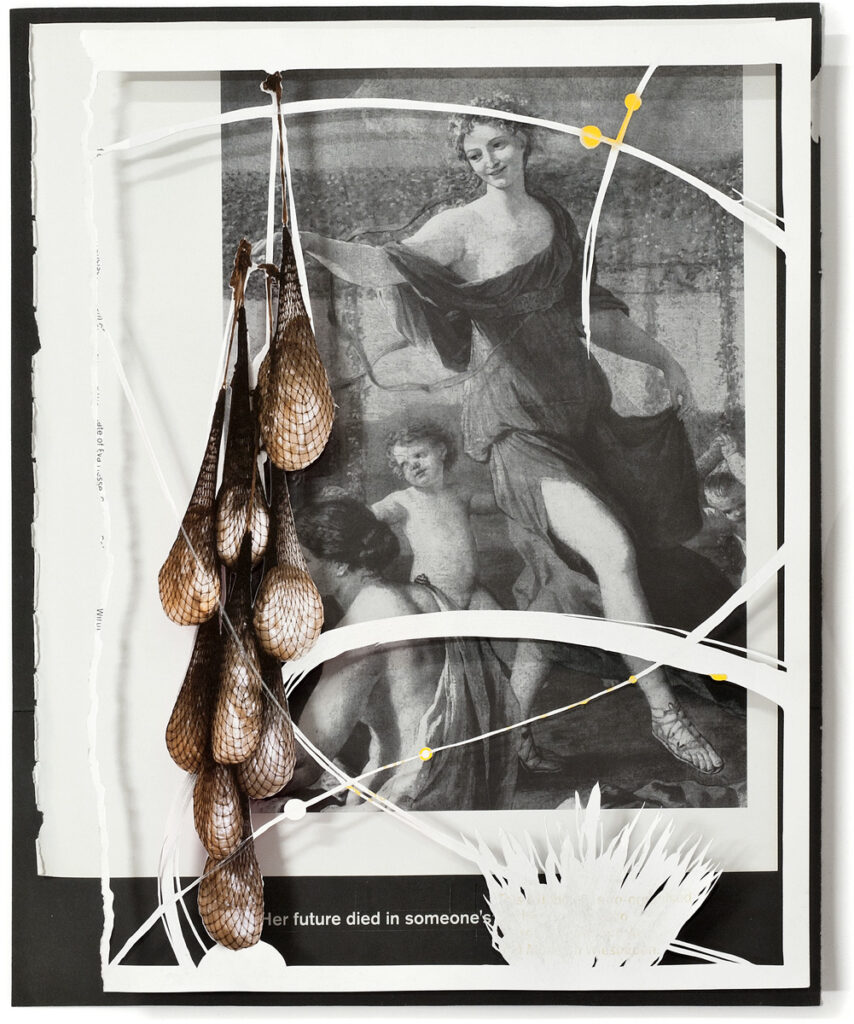

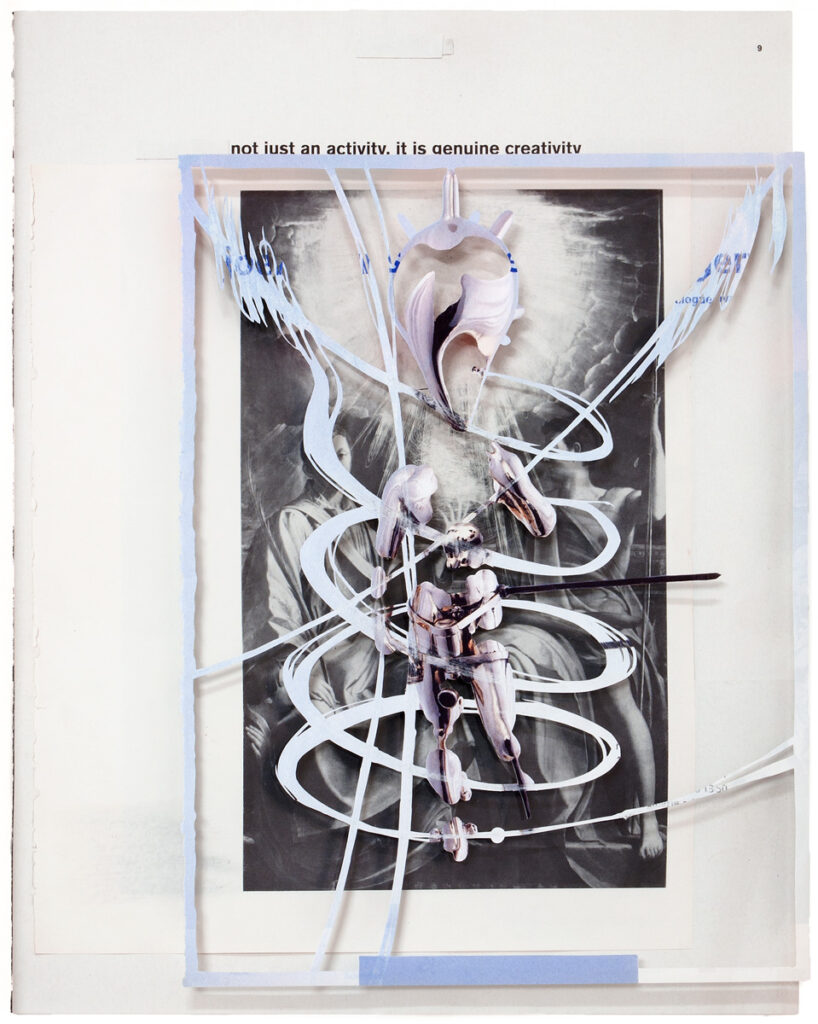

From 2009, Freitag achieved a decisive turning point with the Blattformer project (2009/10). Working analogically with papercuts from advertising magazines, he created new pictorial spaces by removing elements of meaning. Destruction and construction interlock: first the visual worlds are deconstructed, then new orders and forms are developed from the fragments. The Blattformer works function as a repository, a visual archive for subsequent series. In the Star & Poster Cuts (2011–2012), these principles are applied to large-scale works, enhancing their physical presence. The consistent shift from image to objecthood, however, fully manifests only later.

Layering, Reduction, and Erasure (since 2011)

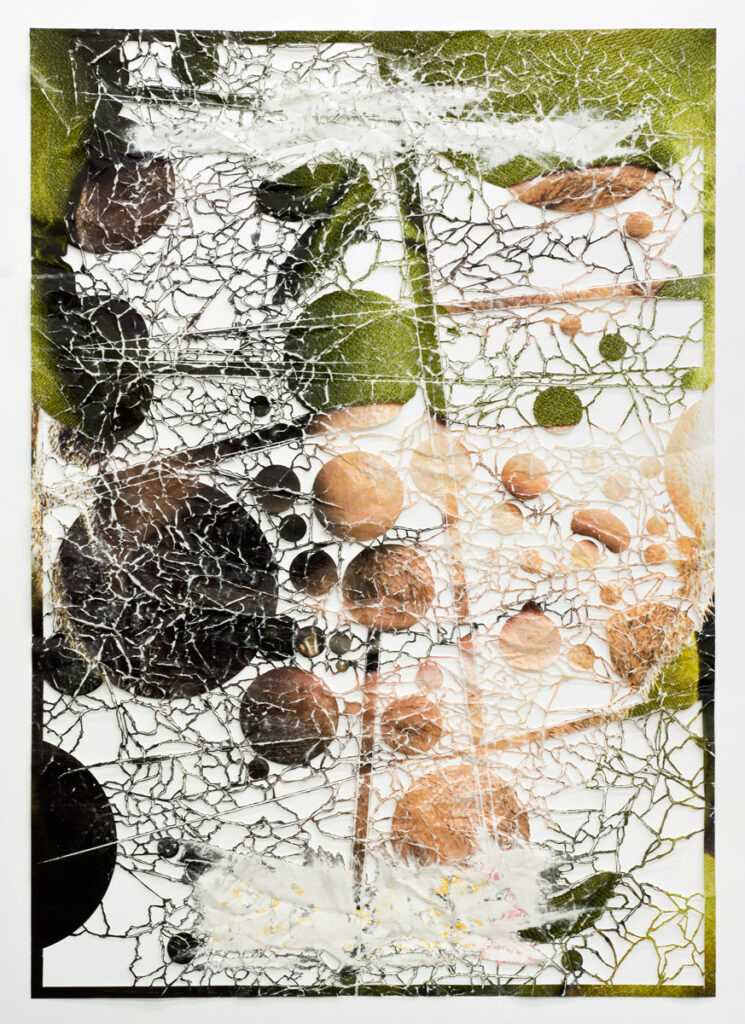

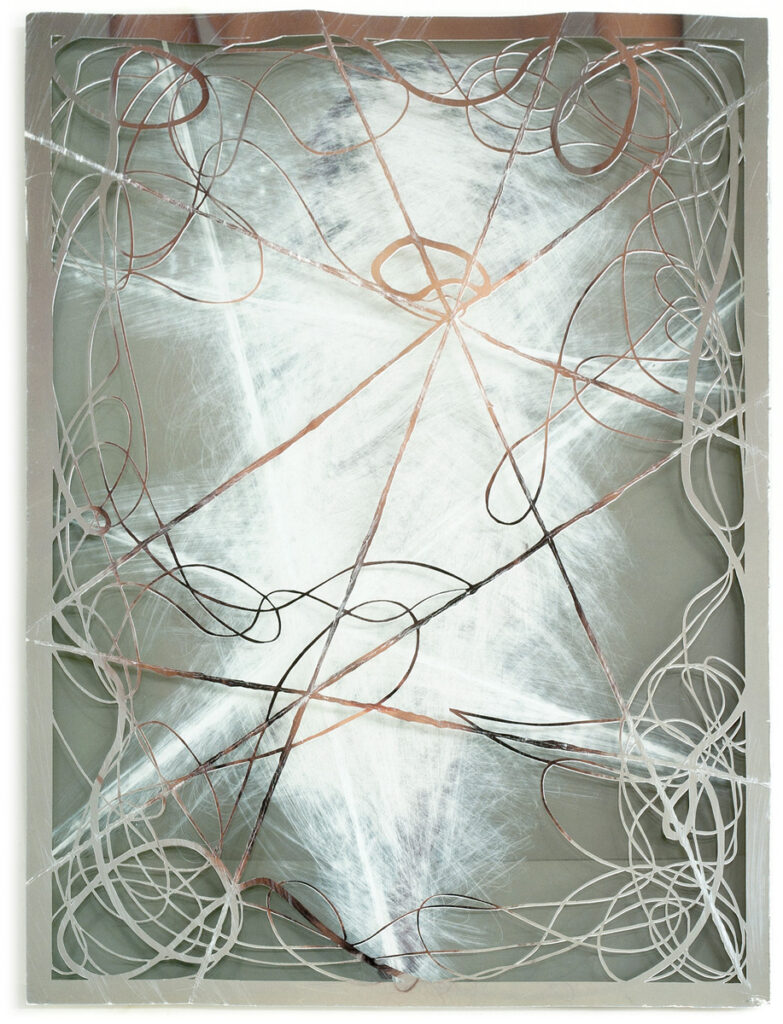

With Nihil Privativum (since 2011), Beauty Free (2013/14), and shocked, I had no idea… (2012–2015), Freitag’s work consolidates strategies of layering and deliberate erasure. Multi-layered collages create depth not through addition, but through subtraction. Meaning is not imposed but fragmented, shifted, and located in the void. The titles open a lyrical dimension in which surface, removal, and projection achieve a tense equilibrium.

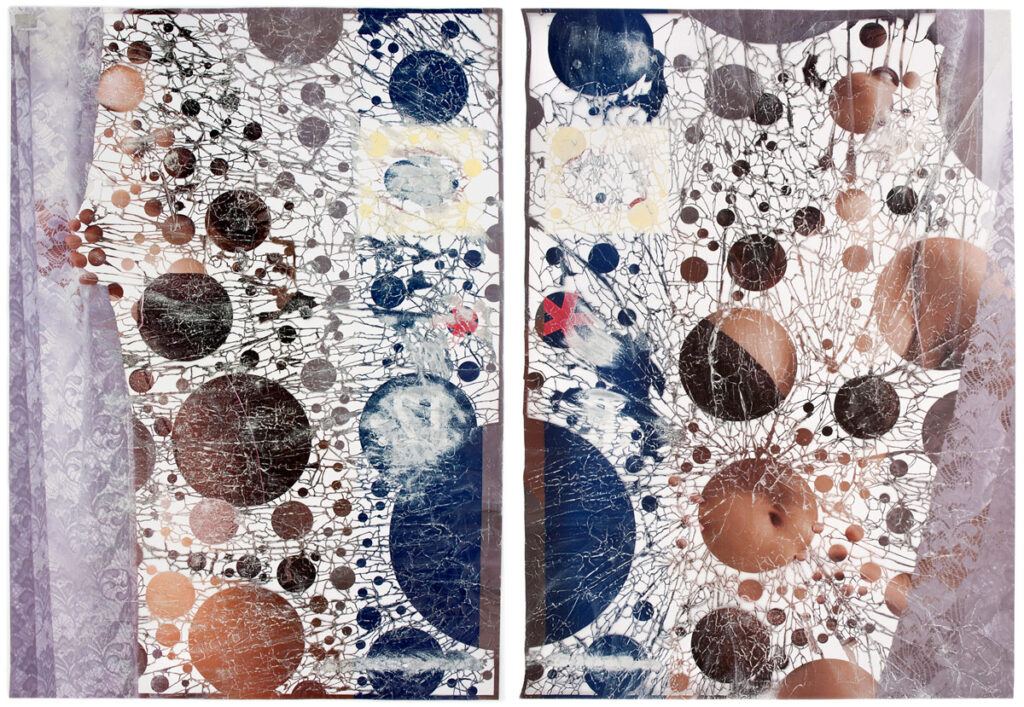

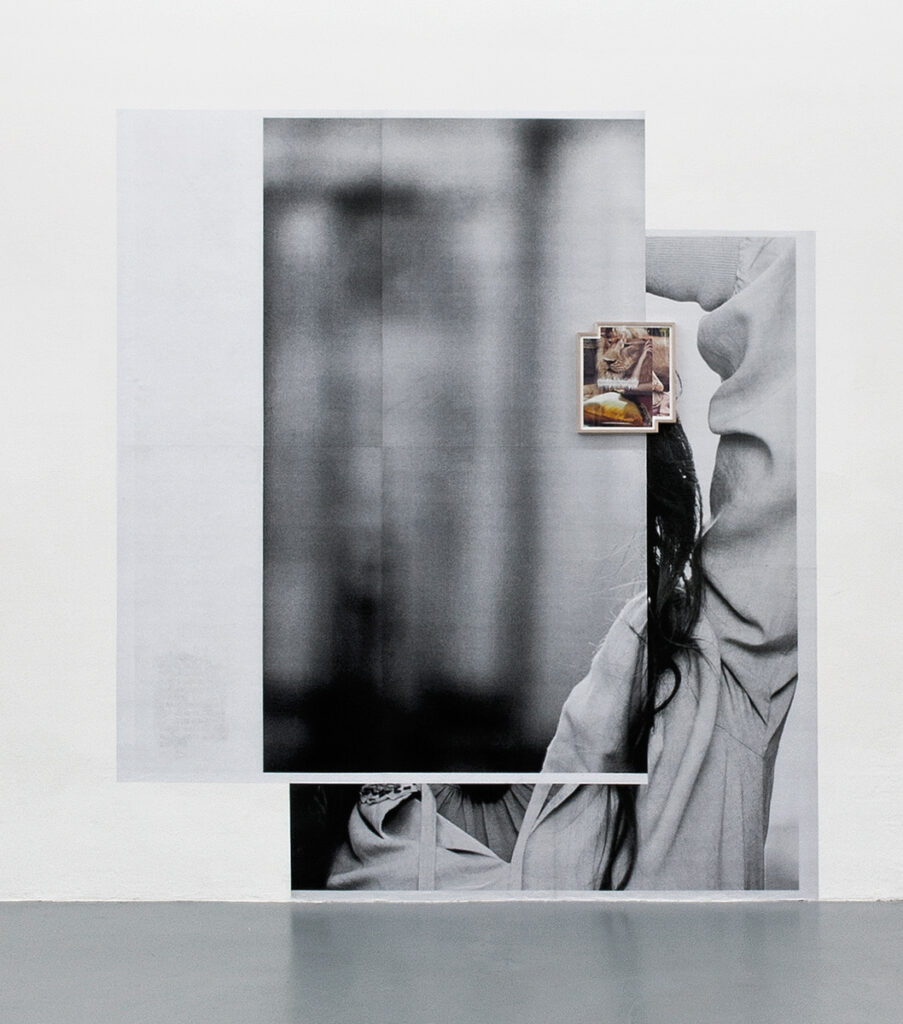

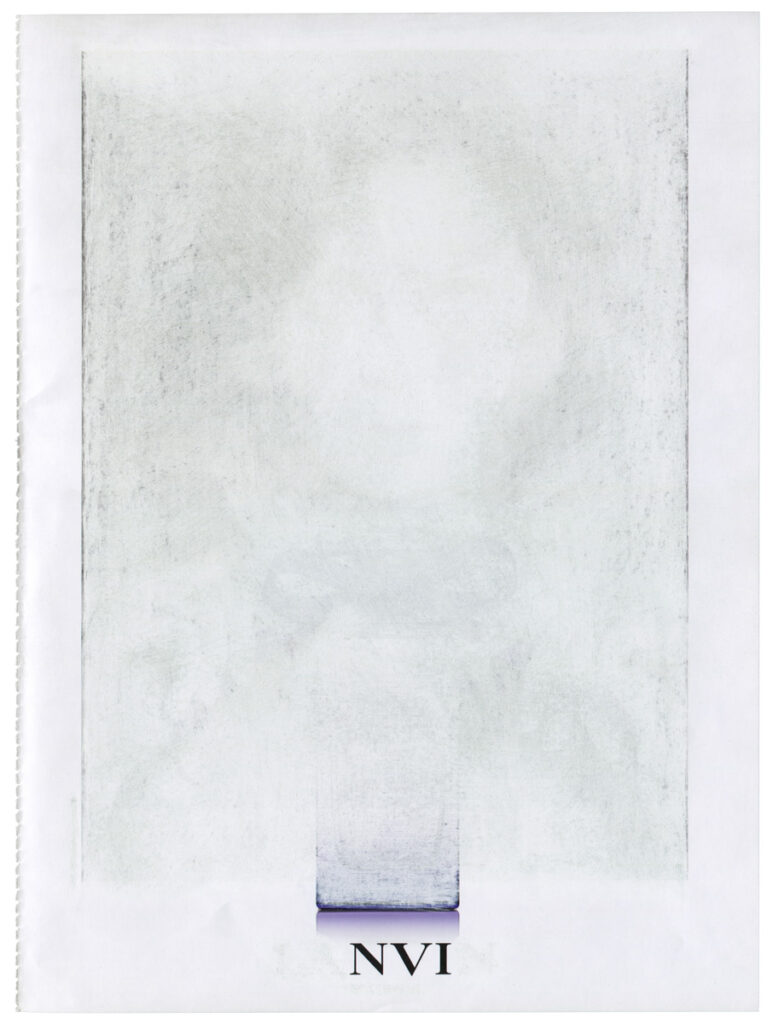

The Big Nothingness (since 2013) occupies a particularly prominent position within this development, marking a conceptual culmination. Here, the means are radically reduced: advertising images are stripped of their central signifiers, and visual information is deliberately erased. Unlike the multi-layered papercuts, collage no longer serves condensation, but reduction—empty spaces dominate the composition and become projection surfaces where meaning only emerges in the act of viewing. With individually adapted frames, the image also asserts itself as a tangible object on the wall. The Big Nothingness thus forms the conceptual bridge to the later mirror- and erasure-based works.

Reflection, Erasure, and Moral Shifts (since 2012)

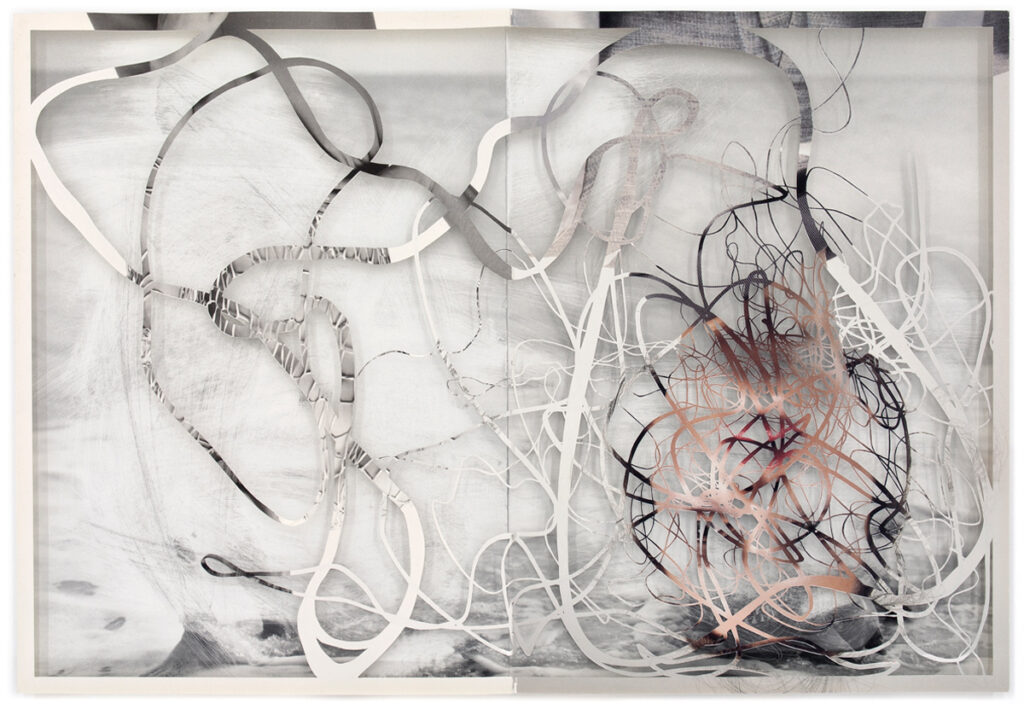

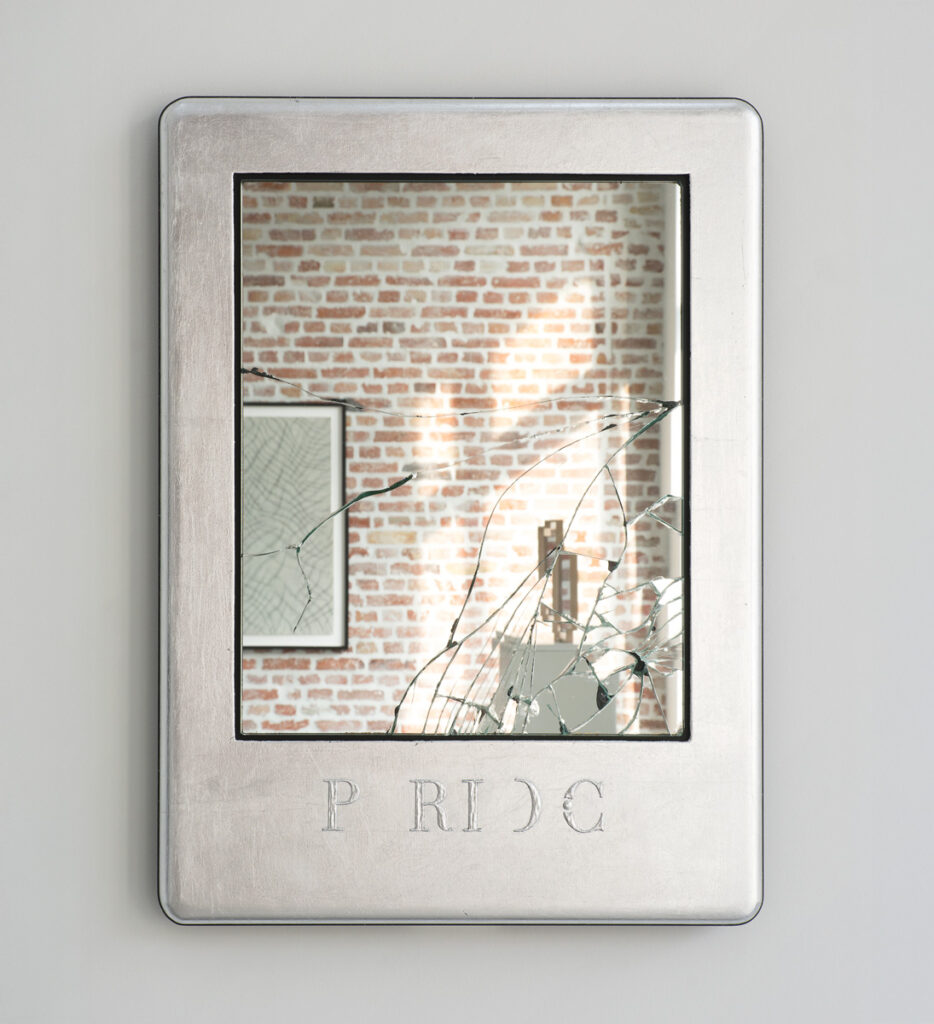

In Egolove (since 2013) and Seven Ways to Win (since 2016), the strategies of erasure and shifts of meaning developed earlier are pursued consistently. Egolove incorporates mirrors as constitutive elements of the image: the viewer becomes part of the work, recognizing themselves within the interplay of image, space, and reflection. Meaning here arises less from the remaining image than from the encounter between work, mirror, and viewer.

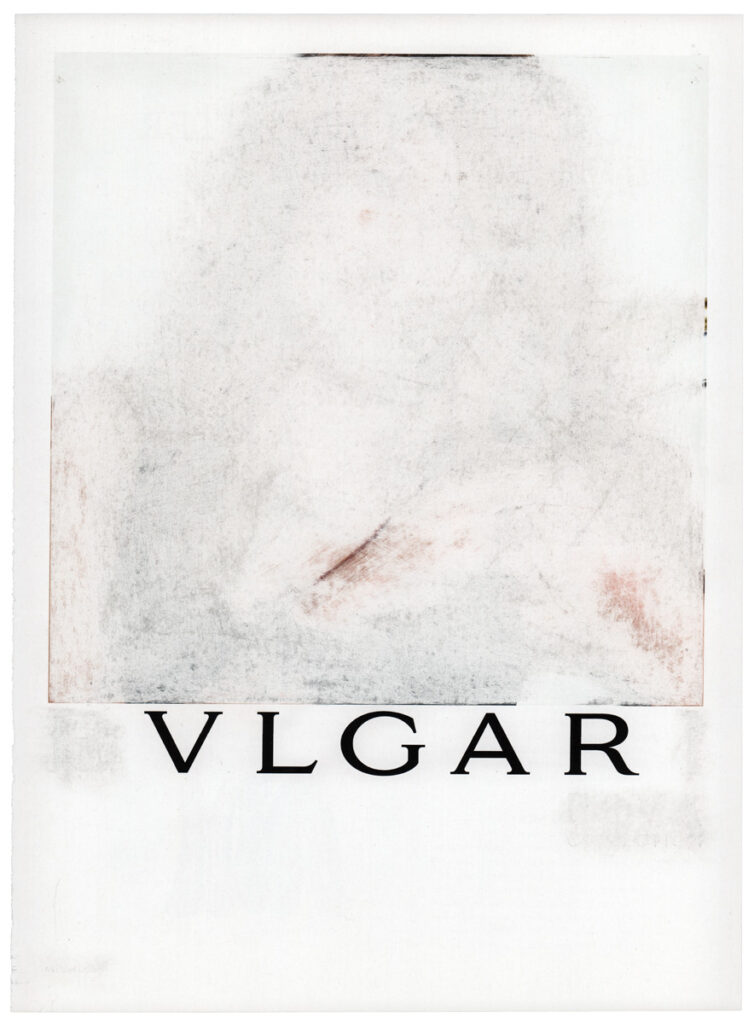

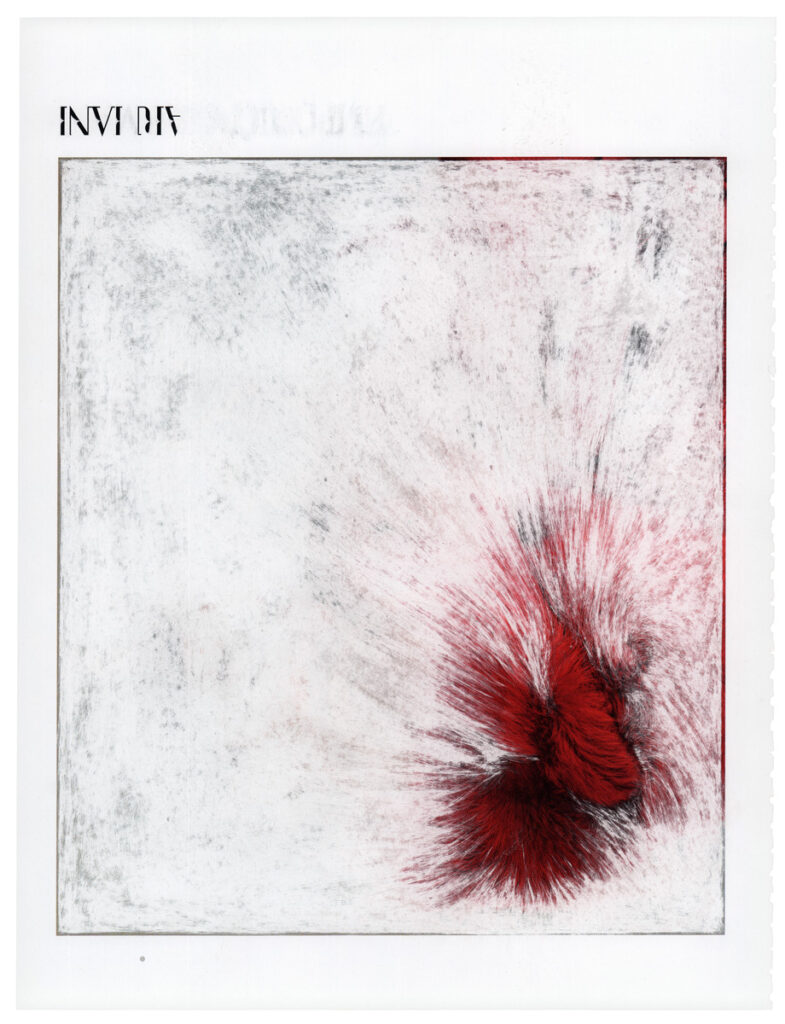

Seven Ways to Win radicalizes this strategy. By reinterpreting brand names and removing images as central signifiers, moral and semantic attributions are shifted. Earlier layering reduces to traces that barely shine through. The pictorial space becomes an open field for projection, where meaning is not fixed but continuously questioned.

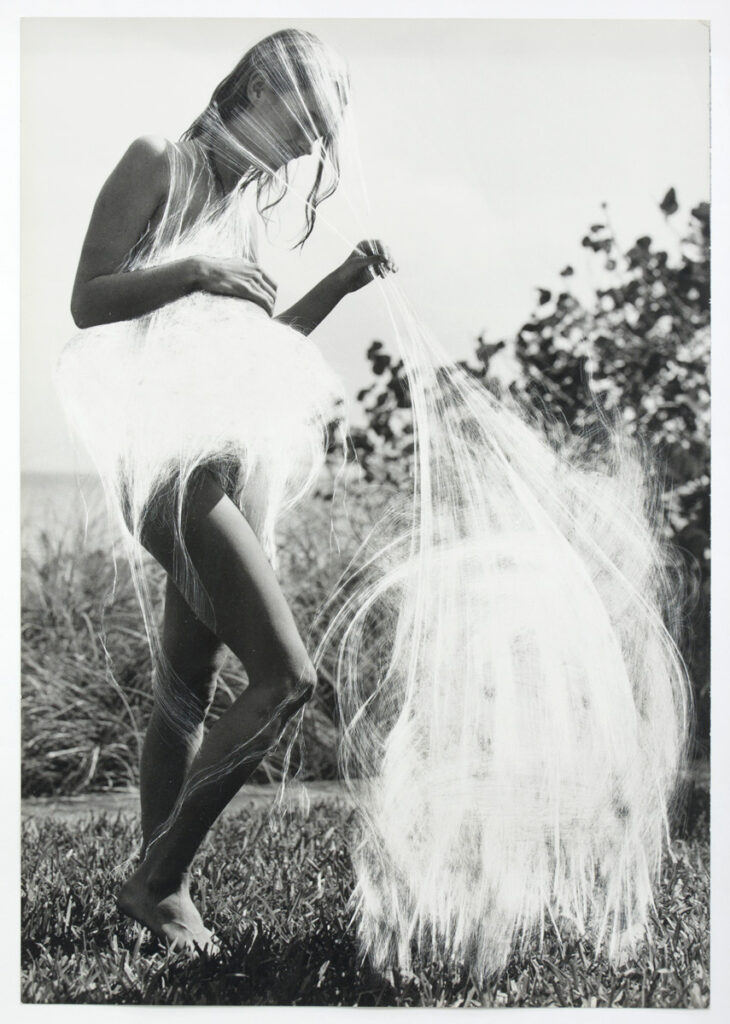

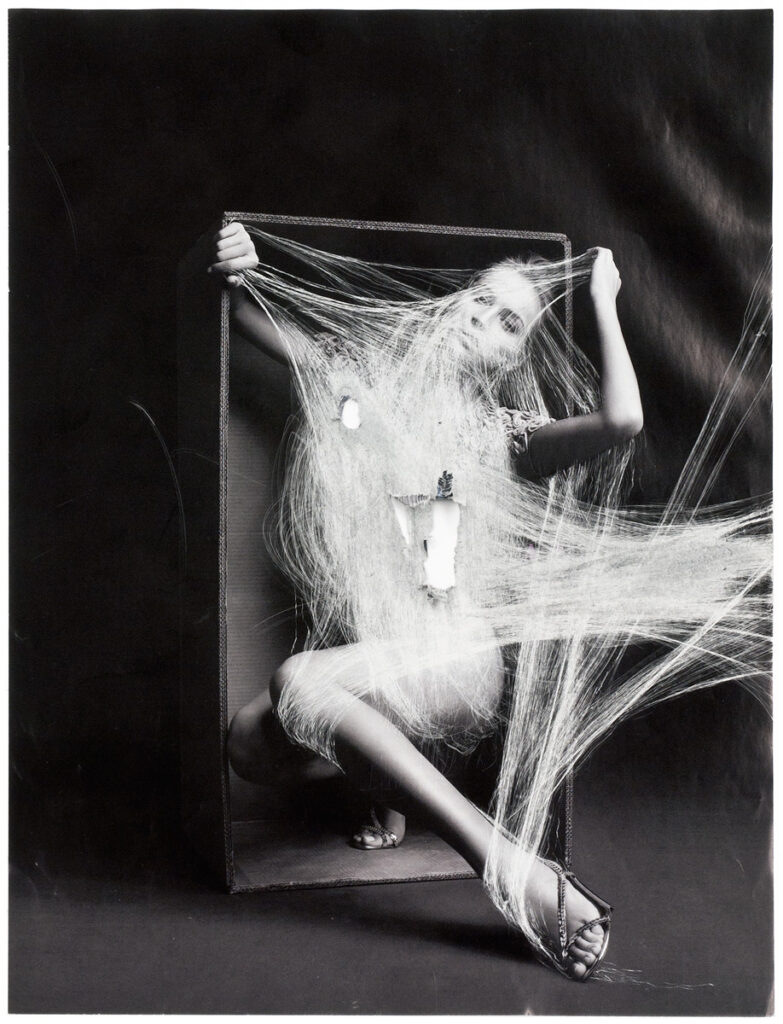

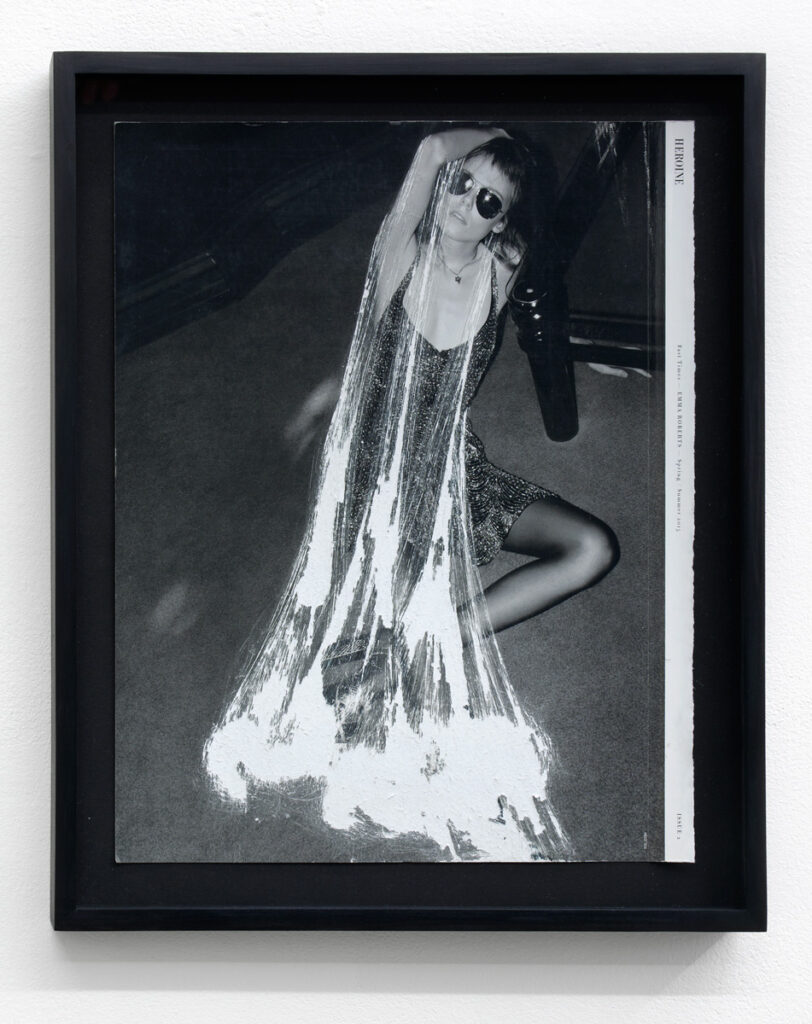

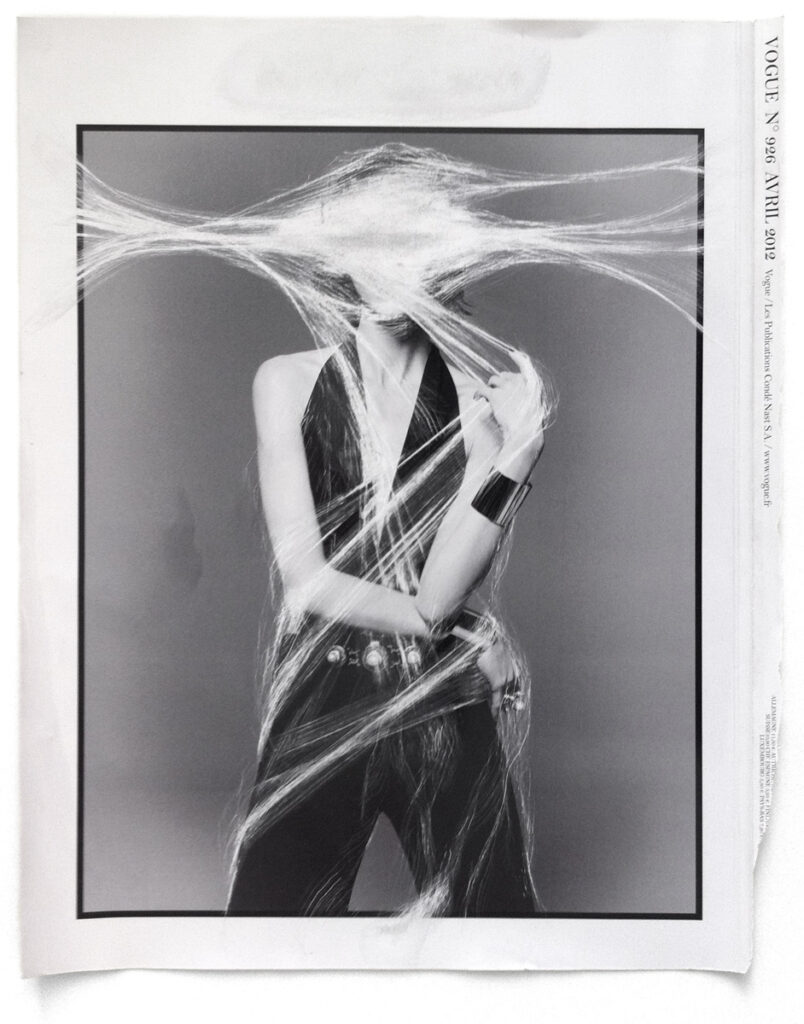

Sandy Candy (since 2012) occupies a deliberately parallel position within this phase. While erasure and removal have long been established as central strategies, this series works again with minimal interventions. Fine scratch marks act as subtle interventions on the existing image material, fully reversing the intended meaning. In its logic, Sandy Candy reconnects with the early Examples for Communication: shifts of meaning are not generated through massive alteration, but through small interventions that overlay an existing image. The works create a bridge back to Peter Freitag’s beginnings, demonstrating that the principle of minimal manipulation and the resulting instability of meaning was present from the outset and continues to resonate in his current work.

Continuity in Change

Across all phases, one constant persists: meaning arises from the interplay of image, context, and perception. Freitag’s works do not provide clear statements but create situations in which meaning must be continuously renegotiated. Through subtraction, displacement, and recontextualization, he reveals the hidden workings of images—and deliberately shifts the responsibility for meaning to the viewer. This retrospective presents a continuous, intensifying investigation into how images generate, lose, and repeatedly re-manifest meaning in their ephemerality.